MEMS Device Test Engineer

Scanning the Microworld: Building and Calibrating a Laser Imaging Platform

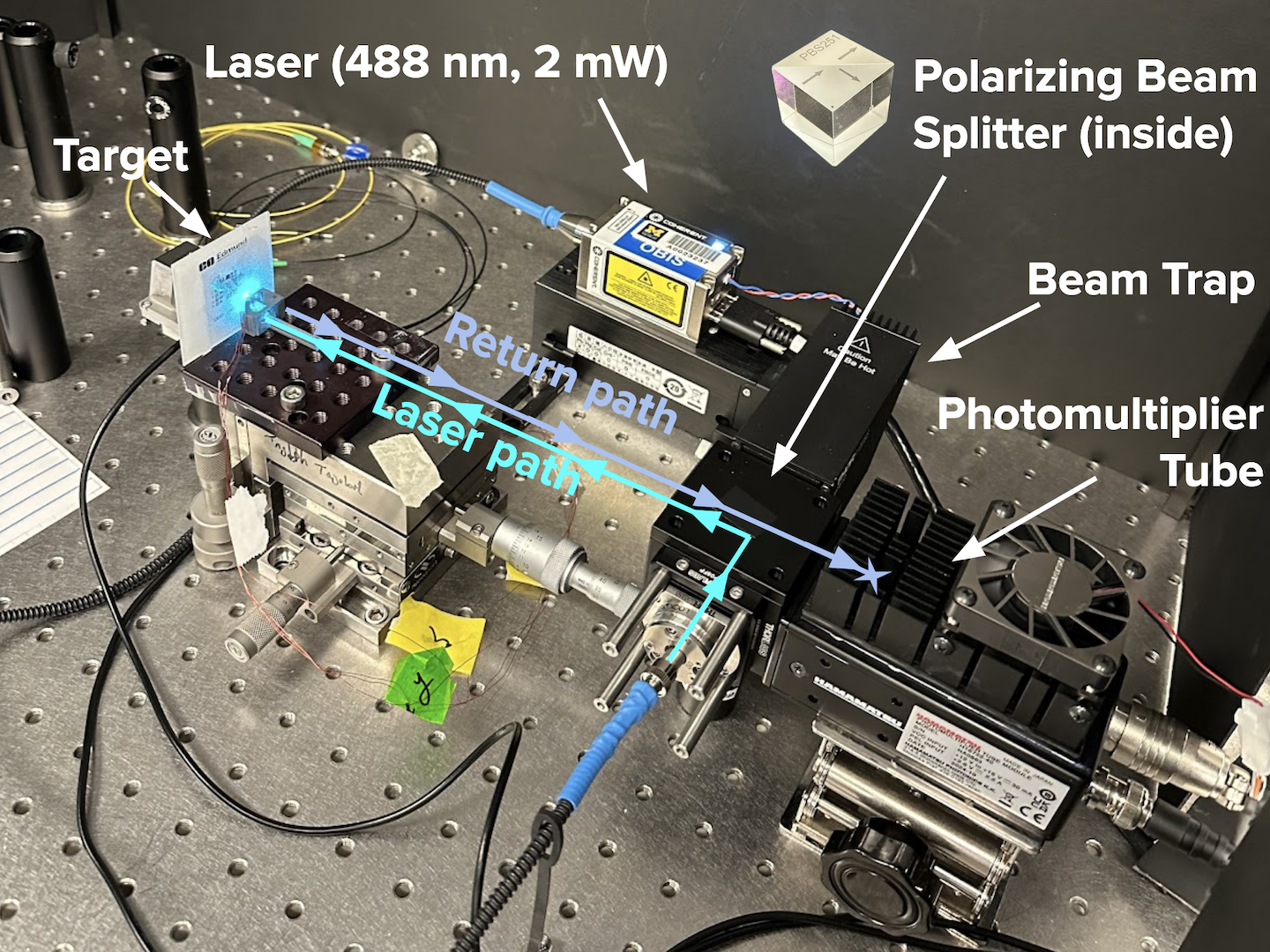

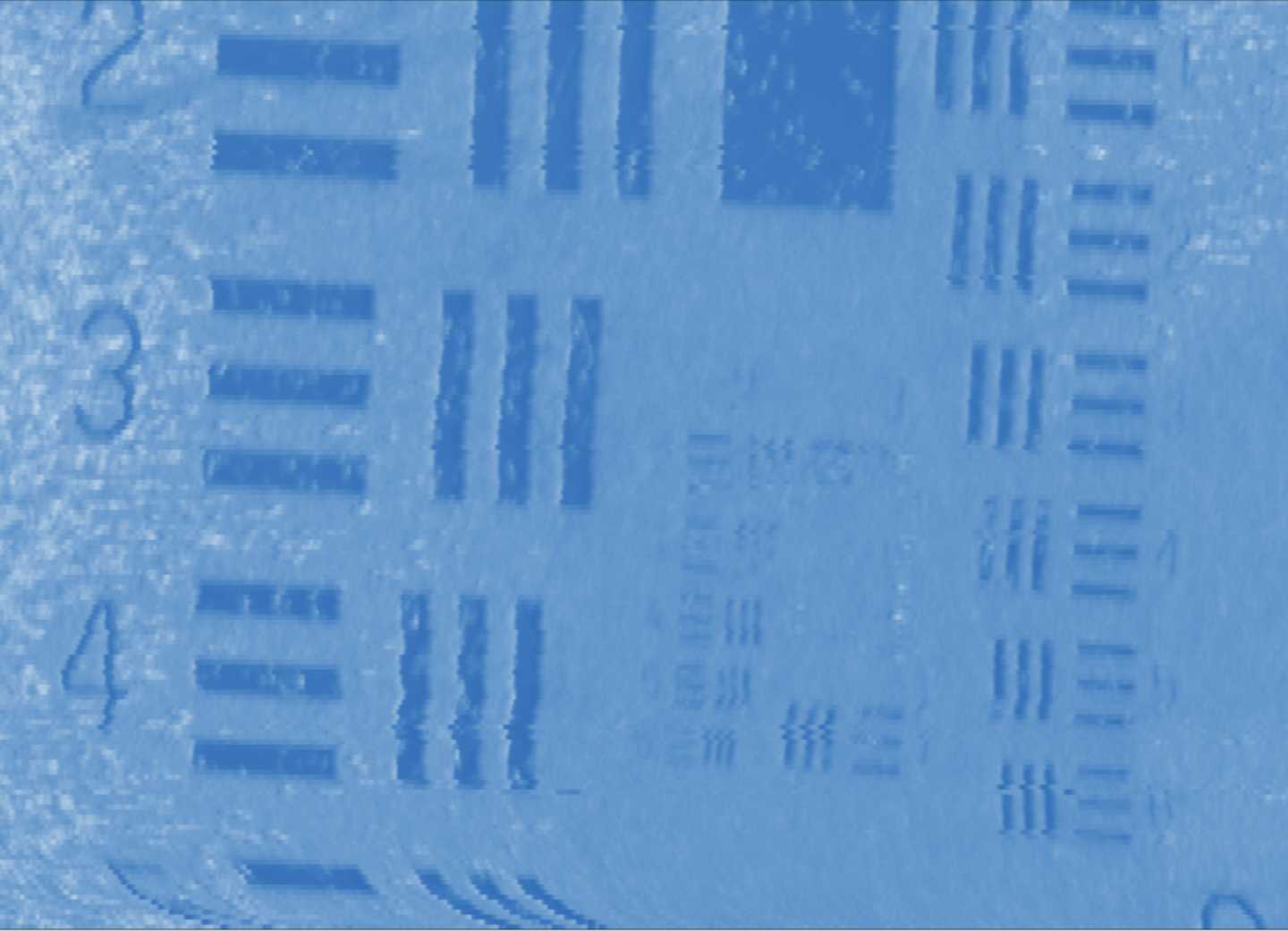

When I joined the Microdynamics Lab at the University of Michigan, I stepped into a space where light, precision, and patience intertwined. My project began as a challenge to build a scanning platform capable of reconstructing microscopic images using a laser, photomultiplier tube (PMT), and piezoelectric stages. The idea was simple in theory: move a laser point across a surface, measure the reflected intensity, and reconstruct an image from the data. But as I quickly learned, achieving stability, precision, and contrast at the micron scale was anything but straightforward. I spent the first few weeks chasing down reflections, fine-tuning polarization with beam splitters, and writing MATLAB scripts to synchronize the motion of the stages with the data acquisition system. Every improvement—each sharper image or faster scan—felt like a small victory carved out of hours of debugging and experimentation.

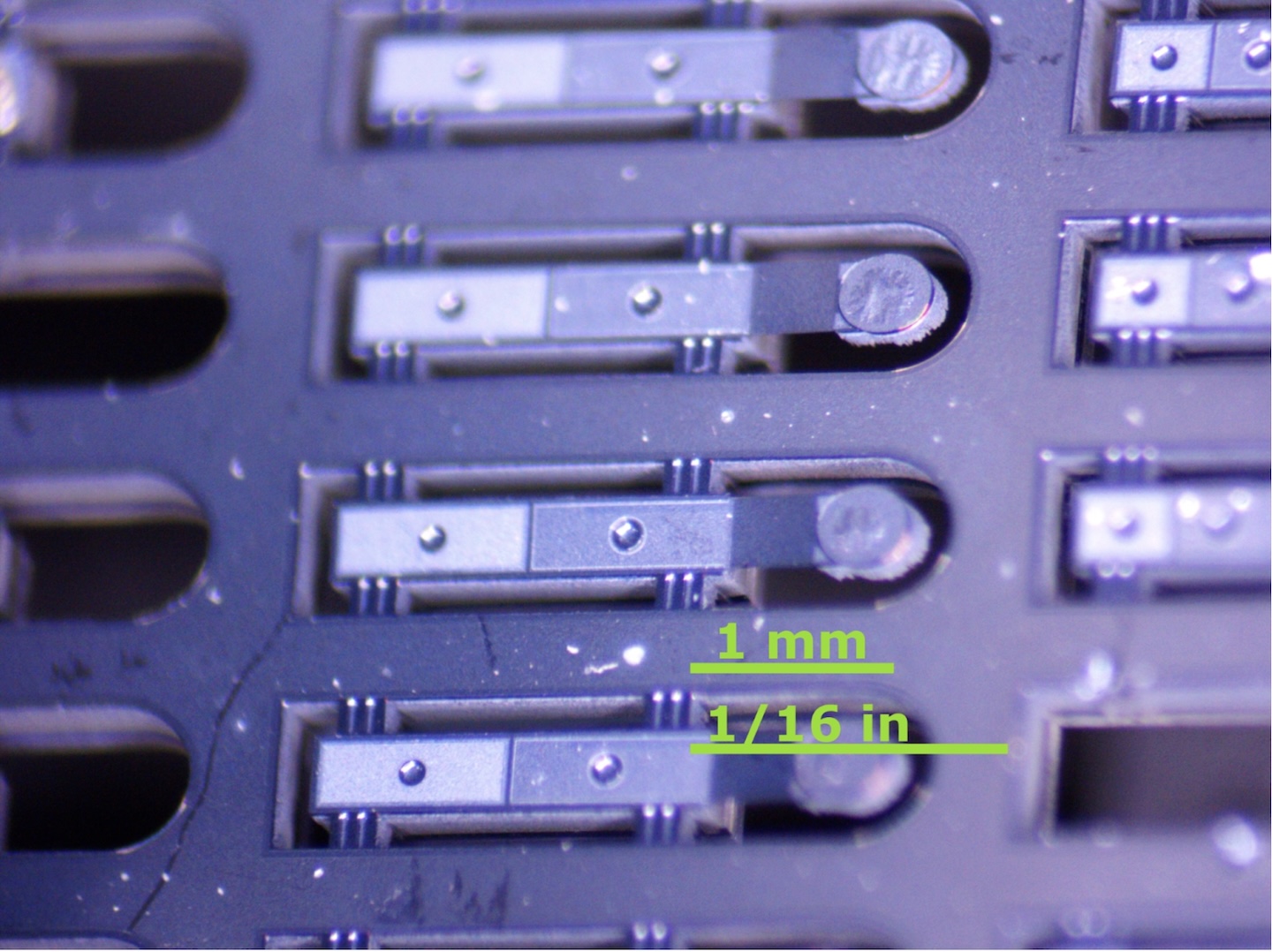

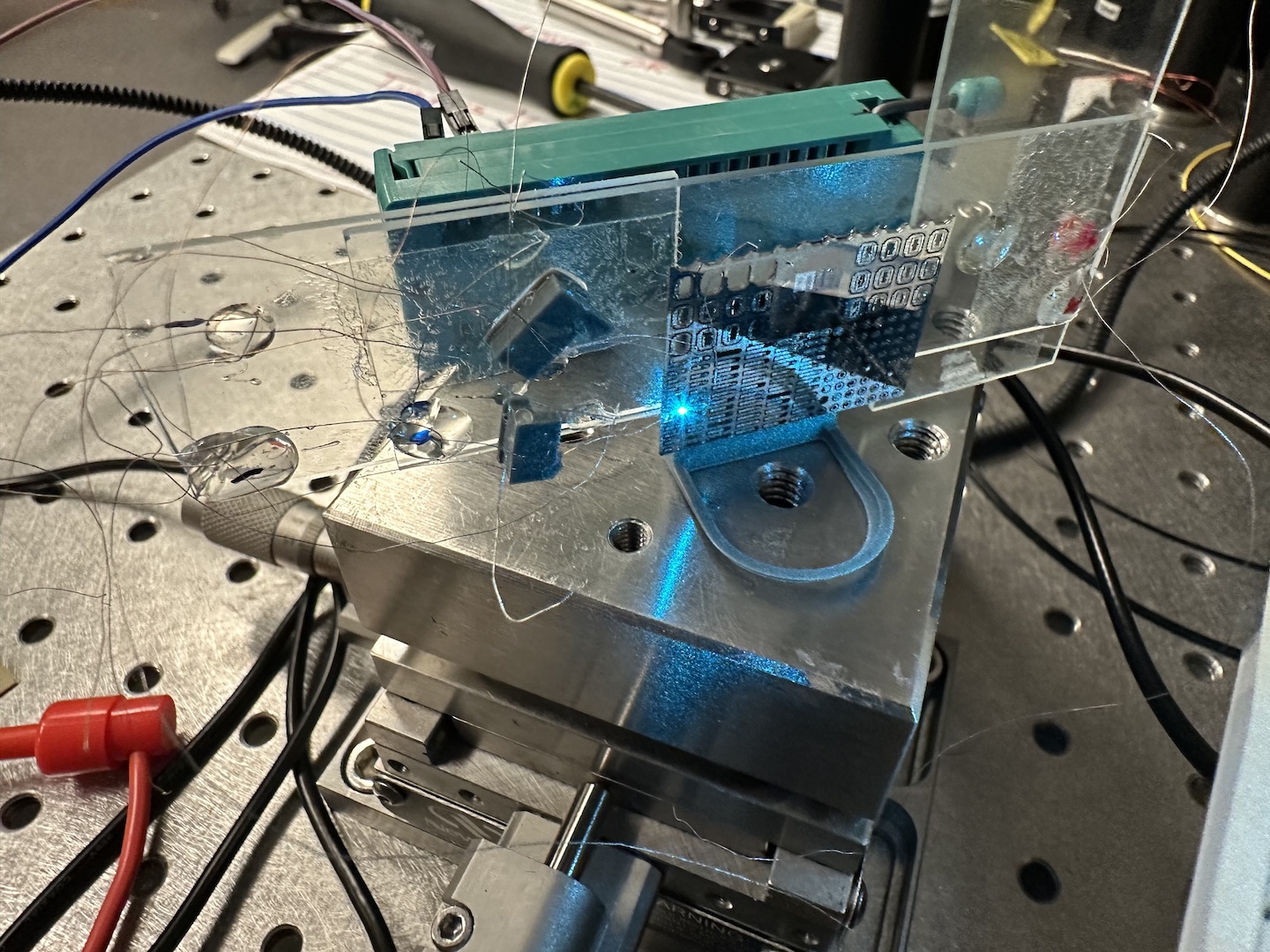

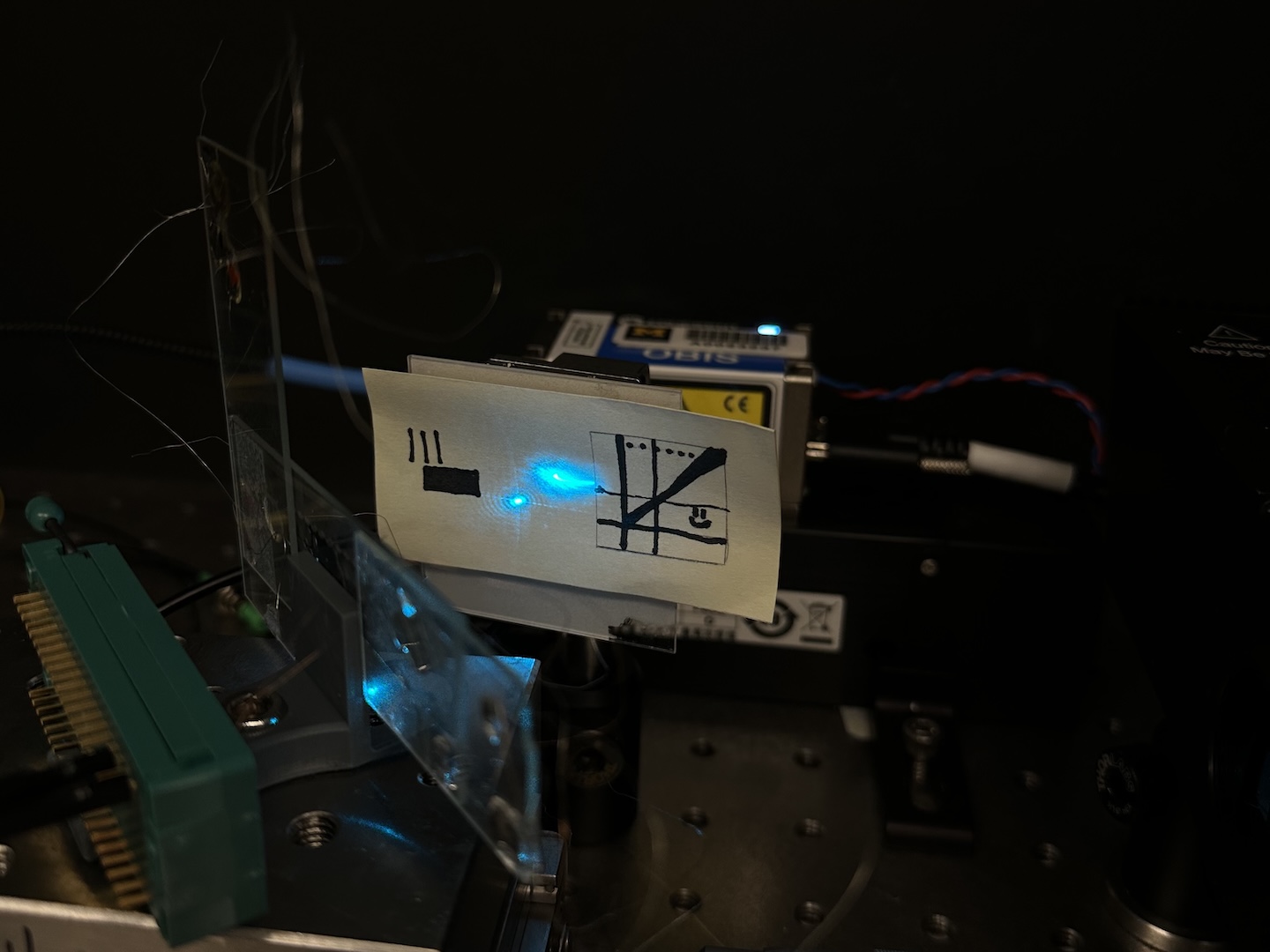

Over the following months, the project evolved from a fragile tabletop setup into a robust optical system capable of resolving details smaller than a human hair. I experimented with control voltages, resistance gains, and scan parameters to maximize contrast while minimizing noise. I implemented continuous scanning techniques, developed calibration scripts to correct for hysteresis, and eventually achieved stable two-dimensional scans with resolutions down to tens of micrometers. Later, I introduced magnification optics and even designed and 3D-printed custom fixtures for components like MEMS mirrors and quarter-wave plates, learning firsthand the link between optical alignment, mechanical design, and signal quality. When the data began to resemble the actual physical targets—grids, symbols, and calibration patterns—it felt like watching the invisible world slowly come into focus.

What I loved most about this experience was the constant interplay between theory and hands-on experimentation. I learned how subtle changes in optics or control code could completely alter the quality of a scan. I became comfortable iterating through failure—broken prints, misaligned optics, saturated sensors—until the system performed as intended. Working in Dr. Oldham’s lab taught me the discipline of experimental precision and the joy of discovery at the smallest scales. It also gave me a new appreciation for how electromechanical systems, from MEMS mirrors to piezo stages, enable the technologies that define modern imaging and robotics.